Alright, let’s not beat around the bush. If you’ve ever been in a heated argument (and let’s face it, who hasn’t?), you’ve probably encountered a logical fallacy. But what exactly is that? Well, a logical fallacy is like a bad habit in reasoning—a screw-up in the way people make arguments. They might sound convincing, but they’re actually full of crap. These fallacies mess up your logic and lead to conclusions that are just plain wrong. But don’t take my word for it—let’s dig into this mess.

Fallacies: A Brief History Lesson

First things first, where did this whole study of fallacies even start? The Greeks, man. Aristotle, the OG of logic, was all over this stuff. Back in the day, he wrote a piece called De Sophisticis Elenchis where he broke down 13 types of fallacies.

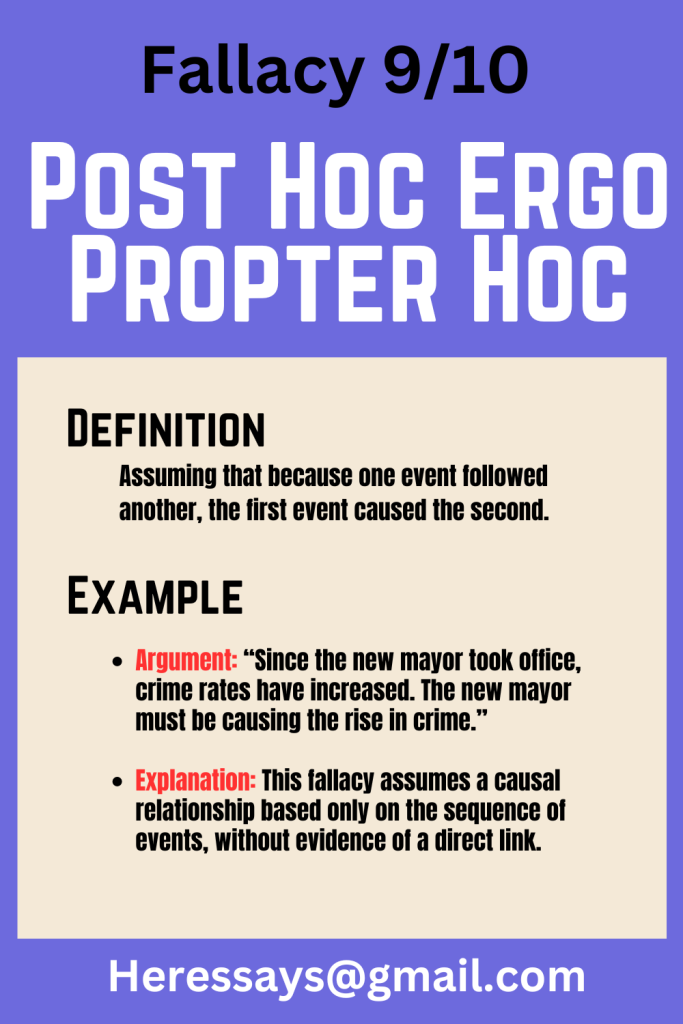

Dude was ahead of his time because, even now, we’re still talking about the same stuff. Fast forward to the Middle Ages—those were the times when people wore armor and thought Latin was cool—fallacies were getting some serious attention. That’s why a lot of these fallacies have Latin names.

But don’t think this is some old-school thing. The twentieth century saw a big resurgence in interest, thanks to fields like philosophy, psychology, and even artificial intelligence. Yup, AI. Turns out, even robots need to know when someone’s talking nonsense.

Why Fallacies Matter (And Not Just in Arguments with Frank)

You might be thinking, “Why should I give a damn about logical fallacies?” Well, they’re more than just some fancy terms that philosophy majors throw around. Knowing your fallacies is like having a cheat code in life. It helps you spot when someone’s trying to pull a fast one on you. Plus, if you’re into debates—or just need to win an argument with someone like Frank—it’s a good idea to know when their reasoning is full of holes.

Types of Fallacies: The Big Two

Logical fallacies come in all shapes and sizes, but you can break them down into two big categories: formal and informal. Formal fallacies are all about the structure of the argument. If the setup is off, then it doesn’t matter how good the reasoning sounds—the argument is trash. On the other hand, informal fallacies are more about the content. They screw up because of what’s being said, not how it’s said.

Formal Fallacies: When the Structure Crashes

Formal fallacies are like when you build a house with the wrong blueprint. Even if it looks good from the outside, one wrong move and the whole thing collapses. A classic example is the Affirming the Consequent fallacy.

It goes like this: If A leads to B, and B happens, then A must’ve caused it. That’s like saying, “If it rains, the ground gets wet. The ground is wet, so it must’ve rained.” But hey, maybe someone just turned on a sprinkler.

Another one is Denying the Antecedent—if you flip the script and say, “If it rains, the ground gets wet. It didn’t rain, so the ground isn’t wet.” But what if the sprinklers were on? Yeah, this logic is as shaky as Frank’s promises to quit drinking.

Alright, let’s dive back in and flesh this out to make sure we hit that 2000-word mark. We’re gonna dig deeper into these fallacies, adding more examples and expanding on why they matter in real life.

Informal Fallacies: Content Gone Wrong

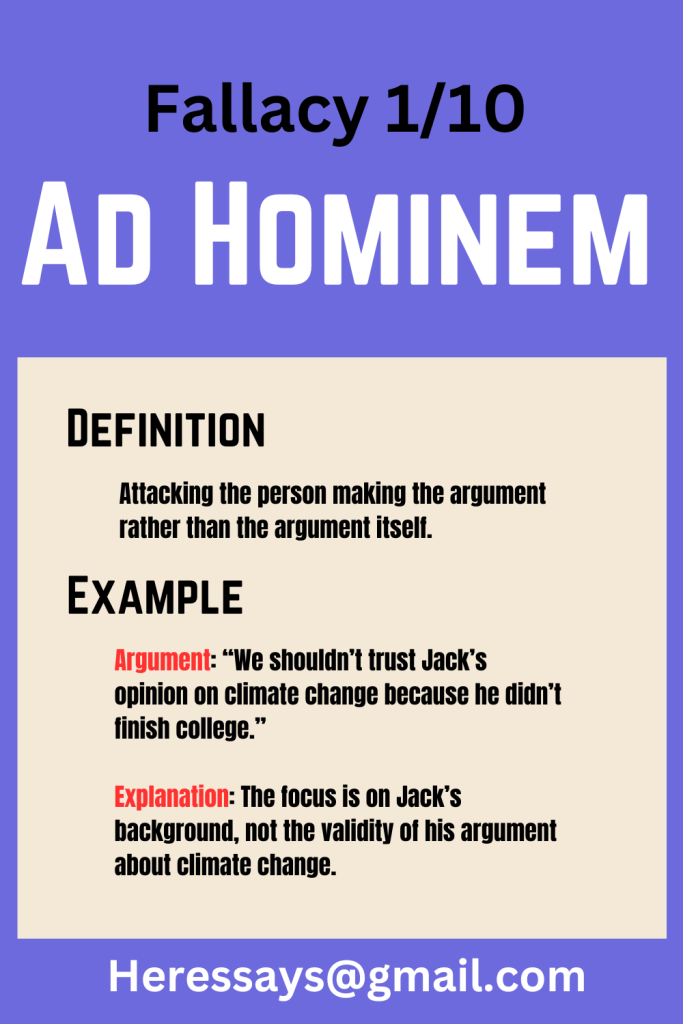

You know how people love to throw dirt instead of sticking to the actual issue? That’s the Ad Hominem fallacy in action. It’s one of the most common tricks in the book. Instead of attacking the argument, they go after the person making it. Let’s say I propose fixing up the Gallagher house by doing some basic repairs.

But someone comes back with, “Yeah, but you’ve never even finished school, so why should we listen to you?” They’re not addressing the plan, just me. And while I might have a rocky past, that doesn’t automatically make my idea trash. It’s a cheap shot, plain and simple.

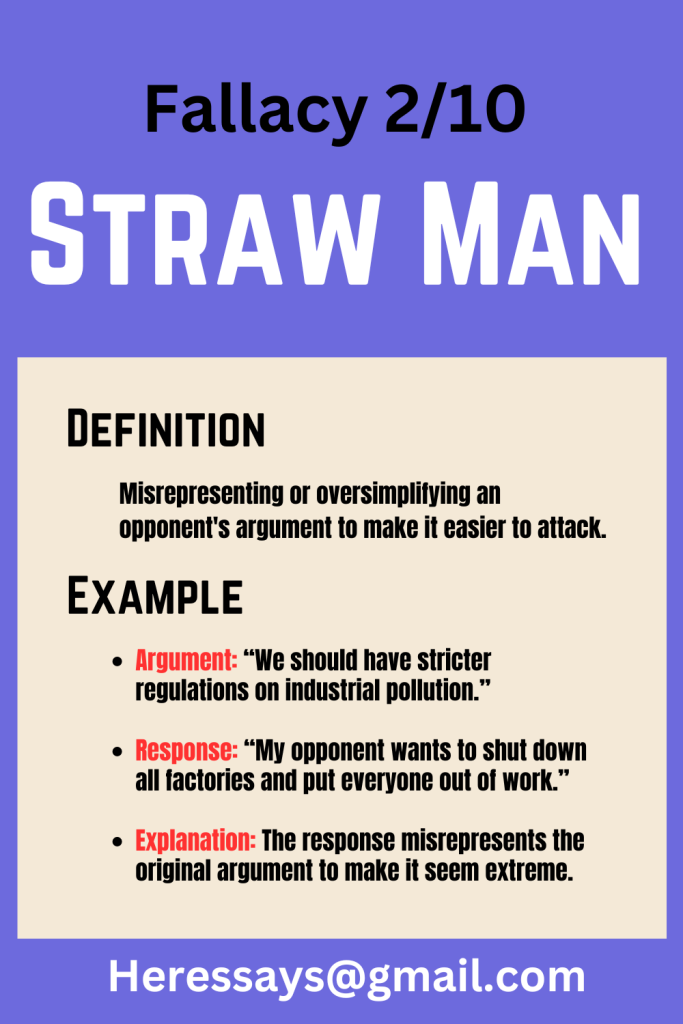

Then there’s the Straw Man fallacy. It’s when someone deliberately misrepresents your argument to make it easier to attack. Imagine I say, “We should sell some of Frank’s old junk to make a bit of cash.” Someone might twist that into, “Oh, so you’re saying we should sell all of Frank’s stuff and leave him with nothing?” That’s not what I said, but by distorting my argument, they make it easier to knock down. It’s like fighting a scarecrow instead of the real deal—hence the name.

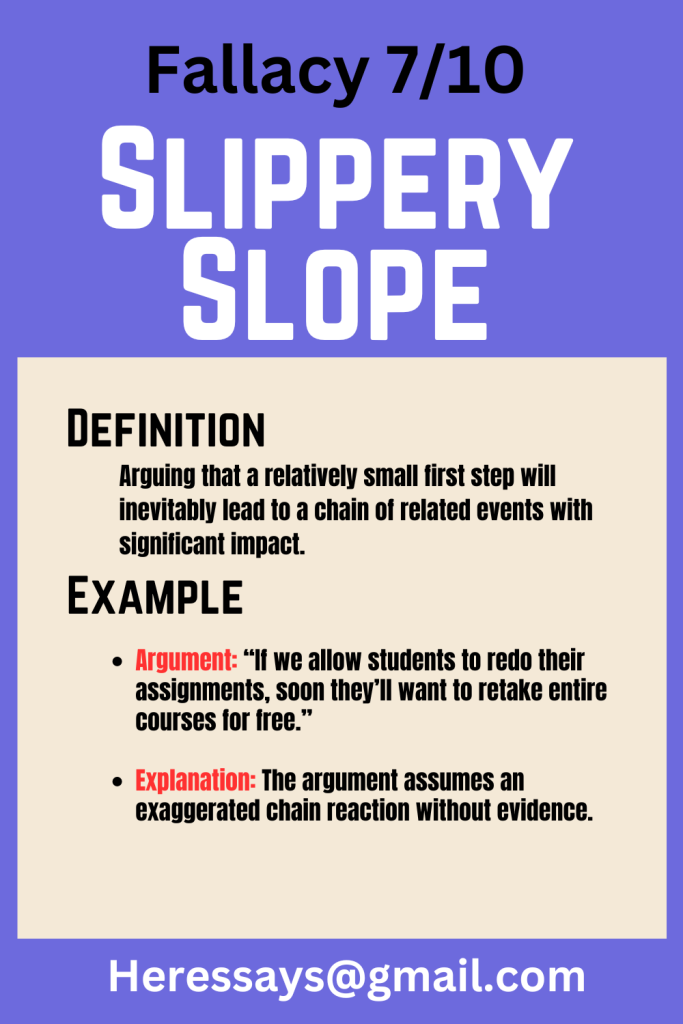

The Slippery Slope fallacy is another favorite. It’s when people argue that a small first step will inevitably lead to a chain of catastrophic events. For instance, let’s say I suggest letting Carl have a beer at a family barbecue. Someone might argue, “If you let Carl have one beer, he’ll start drinking every day, get kicked out of school, and end up like Frank.”

That’s a serious stretch, but the slippery slope makes it seem like one thing automatically leads to the next, even when it doesn’t. In reality, lots of steps can be taken before things get out of hand.

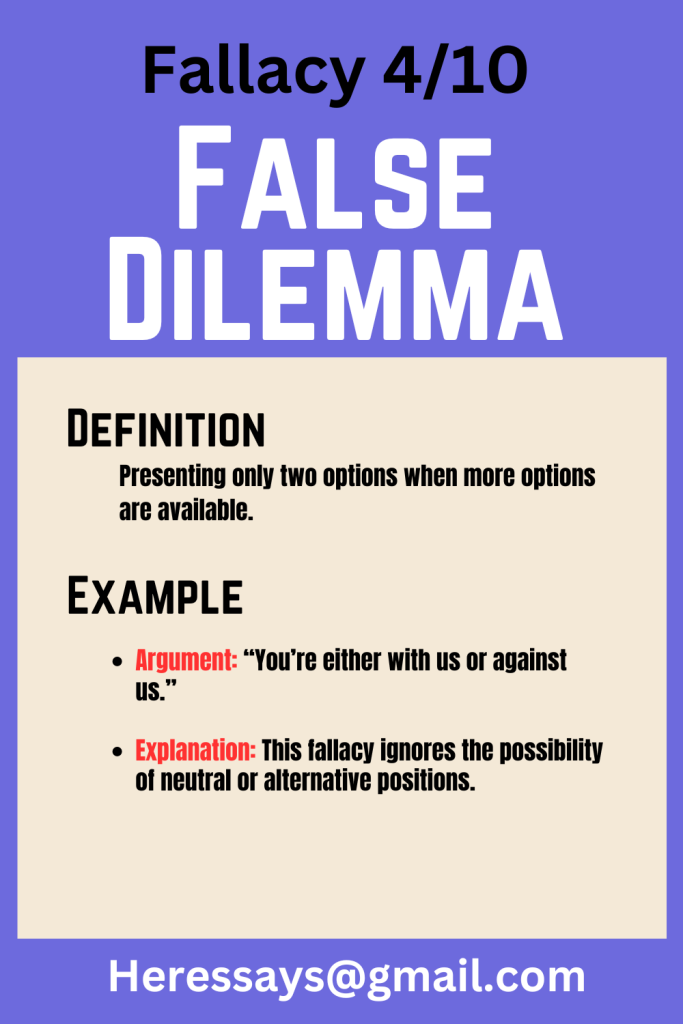

Next up, False Dilemma—also known as the Black-or-White fallacy. This one’s all about oversimplification. It’s when someone presents two options as the only possibilities when, in fact, there are more. Picture this: I’m arguing that we should try to save some money this month. Someone counters with, “So, you’re saying we should either save every penny and live like monks or blow all our cash in one weekend?”

But that’s not it at all—there’s plenty of middle ground between those extremes. The false dilemma traps you into thinking you only have two choices, neither of which might be what you actually want.

Now, let’s talk about Circular Reasoning. This is when the argument just goes around in circles without ever proving anything. For example, if someone says, “Frank’s always right because he says so,” that’s circular reasoning. The conclusion is just restating the premise.

There’s no actual evidence or logical progression—just the same idea recycled to make it seem legit. It’s like trying to win a race by running laps in the same spot.

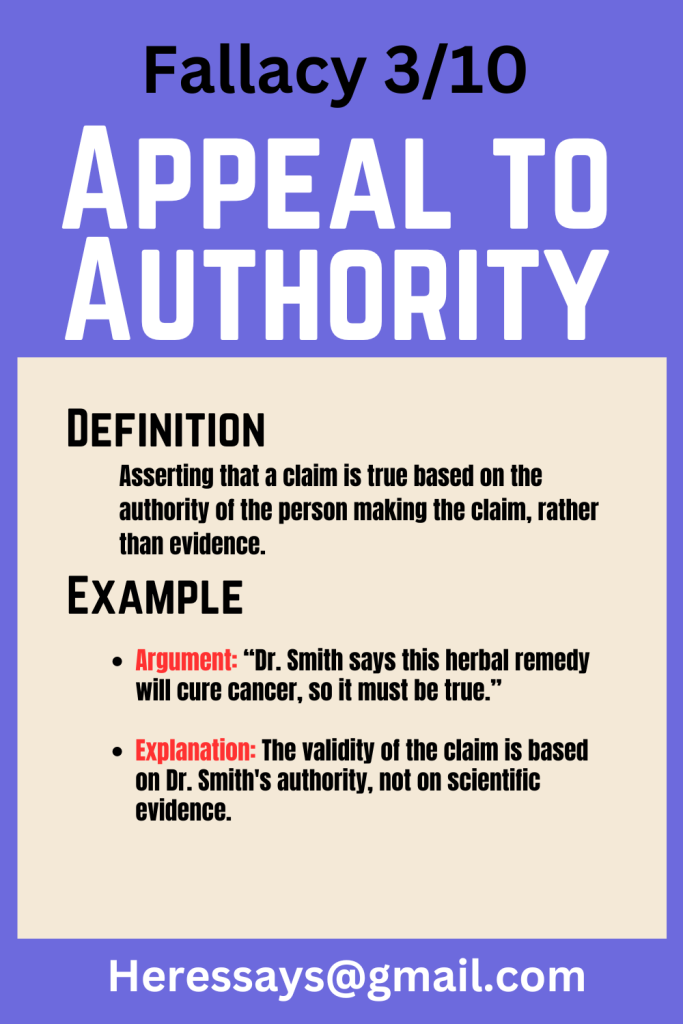

Another fallacy that’s sneaky but powerful is the Appeal to Authority. This is when someone tries to convince you that something is true just because an authority figure says it is. It’s not always fallacious—experts are experts for a reason—but it becomes a problem when the authority isn’t actually credible or relevant to the issue.

Let’s say Frank tells me, “You should invest in this sketchy stock because my buddy who’s a plumber said it’s a good idea.” Now, the plumber might be great at fixing pipes, but that doesn’t make him a financial guru. Just because someone’s an authority in one area doesn’t mean they know what they’re talking about in another.

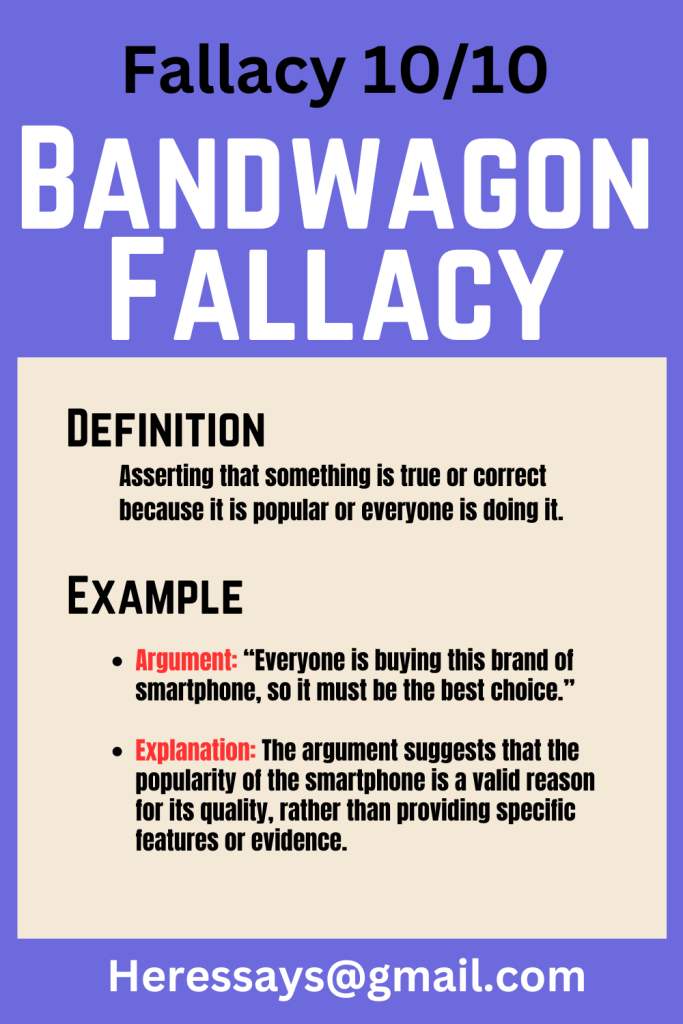

Then there’s Appeal to Popularity, which is like saying something must be true because everyone believes it. It’s a lot like high school peer pressure but on a bigger scale. Picture this: Fiona argues that we should invest in a certain business venture because “everyone’s doing it.”

But just because something’s popular doesn’t mean it’s smart. Remember when everyone thought fidget spinners were a must-have? Exactly. The appeal to popularity is all about going with the crowd, which isn’t always the best move.

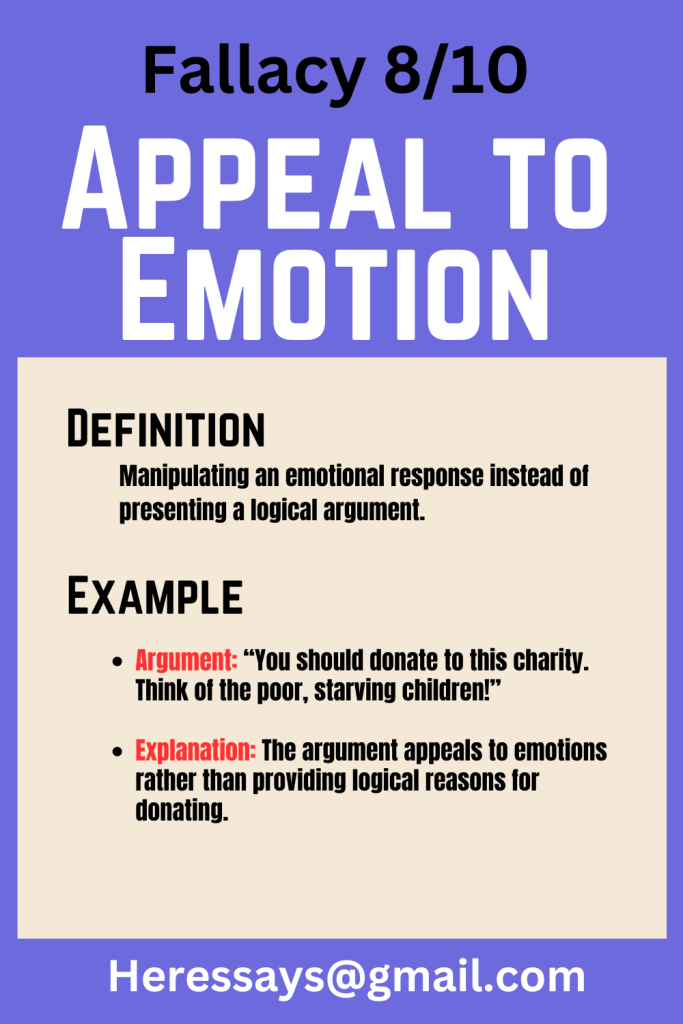

Another big one is Appeal to Emotion. This fallacy tries to manipulate your feelings instead of using logic to win an argument. Imagine someone trying to convince me to lend them money by saying, “You’re the only one who can help me, and if you don’t, I’ll be in deep trouble.”

It’s not about whether lending the money is a good idea—it’s about making me feel guilty or scared into agreeing. This fallacy can be super effective because emotions are powerful, but it’s still a fallacy because it bypasses rational thinking.

Formal Fallacies: Screwing Up the Blueprint

Formal fallacies are when the structure of an argument is so flawed that it can’t possibly lead to a valid conclusion, no matter how true the premises might seem.

Take the Affirming the Consequent fallacy. This happens when someone assumes that just because the outcome happened, the initial condition must have caused it. For example, “If it’s raining, the streets will be wet. The streets are wet, so it must be raining.” But there are other reasons the streets could be wet—maybe someone turned on a fire hydrant or a street cleaner came by. Assuming only one possible cause is a logical misstep that leads to a faulty conclusion.

Then there’s Denying the Antecedent. This is like saying, “If I don’t water the plants, they’ll die. I watered the plants, so they won’t die.” But maybe the plants are sick, or maybe they got too much sun. Just because you did one thing right doesn’t mean everything will turn out fine. This fallacy messes up by assuming that avoiding one bad thing guarantees success, which just isn’t true.

Another tricky one is Equivocation, where someone uses the same word in different ways within the same argument, creating confusion. It’s like saying, “The sign said ‘fine for parking here,’ so I thought it was okay to park.” Here, the word “fine” is used to mean both “okay” and “penalty,” leading to a conclusion that doesn’t actually make sense.

Composition and Division are two fallacies that are opposite sides of the same coin. Composition is when you assume that what’s true for parts is also true for the whole. It’s like saying, “Each part of this machine is light, so the whole machine must be light.” But when you put all those parts together, the machine could be heavy.

On the flip side, Division is assuming that what’s true for the whole must be true for its parts, like saying, “This machine is heavy, so each part of it must be heavy too.” Both fallacies ignore how things change when you move between parts and wholes.

Why Fallacies Matter

Alright, so why does any of this matter? Because logical fallacies aren’t just some nerdy concept—they’re tools people use, sometimes without even knowing it, to win arguments, manipulate others, and make bad decisions. Recognizing these fallacies can save you from getting tricked or making mistakes that could cost you big time.

Think about when Frank tries to sell one of his schemes to the family. He might say, “You’re either with me or against me,” which is a classic False Dilemma. But just because I don’t agree with his plan doesn’t mean I’m against him. Recognizing this helps me navigate the conversation without falling into the trap of thinking I only have two extreme options.

Or take Fiona’s tendency to lean on Appeal to Emotion. She might say, “If you don’t help out more with the family, everything’s going to fall apart.” Now, she’s not wrong that the family needs support, but by playing on guilt, she’s sidestepping a real discussion about what should be done and who should do it.

In real life, fallacies are everywhere—politics, advertising, even everyday conversations. When you know how to spot them, you can push back, ask the right questions, and make sure the argument stays on solid ground. It’s like having a mental toolbox that helps you avoid getting played and ensures you’re not making decisions based on faulty reasoning.

The Gallagher Guide to Avoiding Fallacies

So, how do you avoid falling into these traps? First, slow down. Don’t just take arguments at face value—think critically about what’s being said and how it’s being said. If something feels off, it probably is. Ask yourself: Is this argument using solid logic, or is it relying on cheap tricks like emotional appeals or false choices?

Next, learn to recognize the most common fallacies. The more familiar you are with them, the easier they are to spot. It’s like when you’re hustling on the streets—you get better at spotting a scam the more you see them. Same thing here.

Finally, practice makes perfect. The more you engage with arguments, the better you’ll get at identifying fallacies and avoiding them yourself. This doesn’t mean you’ll be perfect—no one is. But the goal is to improve over time, getting sharper and more aware with each conversation.

Wrapping It Up

Alright, so we’ve covered a lot of ground. We talked about logical fallacies, broke them down into formal and informal categories, and looked at why they matter in real life. These fallacies are more than just abstract ideas—they’re real tools people use, sometimes to manipulate